I typically focus on the behavior and training of cats and dogs. Cats and dogs are popular, common pets and more likely to display behavior problems or training deficits in need of professional attention. However, our littler pets of various species also learn and can be trained using many of the same principles one might use with a dog or cat. Let’s consider some things we might teach our scaled, finned, or feathered friends and how we would go about training them. I will use for example those critters who live in my own home.

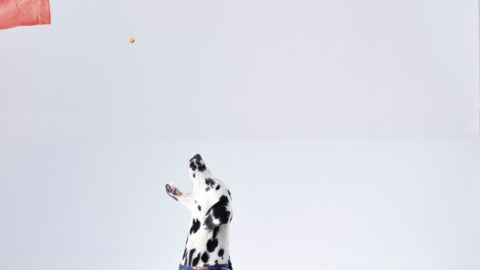

In addition to our three dogs, my family has a Siamese fighting fish, an electric blue crayfish, three platies, a yellow-collar miniature macaw, and a bearded dragon. Each of these critters is able to learn and respond to positive reinforcement. For the fish and the crayfish, food is the reinforcer we use. Our crayfish prefers to spend much of his time in his underwater cave but we like to watch him move about the tank, so my children and I have taught him that in order to earn his pelleted food, he must come out of his cave. About twice a day, Blueclaw thus comes marching out, claws extended, waiting to be rewarded for showing himself. We’ve taken it a step further with our Siamese fighting fish, Zoomer, and have taught him to jump out of the water to nibble food from our fingertips. We started by dropping his food into the top of his tank from our fingertips, then used a moistened finger tip to hold the food to it until Zoomer came to the top of the water, and eventually until he jumped clear out of the water to reach the food. Now our Zoomer is also a colorful and enthusiastic jumper and his nibbling kisses to our fingertips are a delight to my young children.

As we move along to more complicated critters, such as our bearded dragon and our parrot, both the rewards that can be used in training and the responses that can be taught become more complicated as well. Our parrot, Sappho, has learned to say “Hello!” as a request for social interaction and “Step up!” as a request to get out of the water after her bath or when she wants to be picked up in general. She has learned to play chase and catch with balled up pieces of paper or small toys. In fact, she sits here now at my desk as I type, chatting and trying to entice me into another round of play. Of course, parrot owners more creative than me have taught their feathered friends a variety of vastly more complex and clever responses, and parrots are in fact considered some of the most intelligent creatures of the animal kingdom.

We are teaching our young bearded dragon, Metalmouth, to tolerate and even enjoy handling and being carried around on a shoulder or chest. At this stage, we are working first on teaching Metalmouth that human touch is associated with food, so we feed him his mealworms, kale, and cilantro treats by hand and pet and talk to him as he eats.

In each of these cases, we utilize four strategies that I often recommend to cat and dog owners as well. First, we rely on consistency – for example, presenting the same hand cues repeatedly so that the animal comes to learn that certain movements by us predict certain options for him. Second, we rely on positive reinforcement in the form of food, play time, or snuggling provided when certain desirable responses occur. Third, to teach more complex responses, we utilize shaping, which involves beginning with easy and simple responses and rewarding those repeatedly before gradually moving toward more complicated or challenging responses. Fourth, we use systematic desensitization, which allows animals to get used to human handling and interaction in small stages while their fearful behavior is gradually replaced with more confident and relaxed behavior around us.

Whether it’s a hamster, an iguana, a ferret or a fish, pets in various shapes and levels of complexity can learn all sorts of fun tricks and useful responses. They can be taught to look forward to their interactions with their human handlers as a highlight of their day. In many cases, the responses one can teach their small pet are limited not by the pet’s intelligence or ability to learn but instead only by our own creativity and perseverance.

Megan E. Maxwell, Ph.D., CAAB